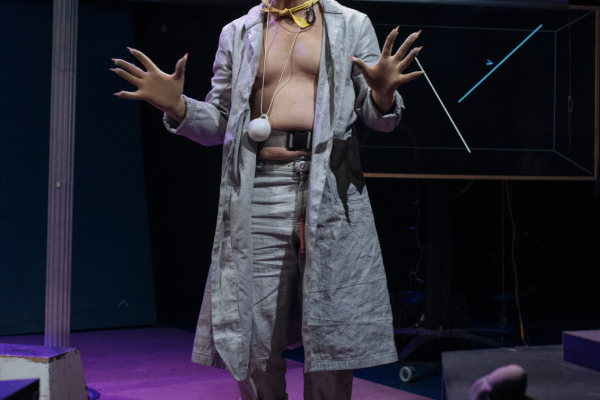

The president of the United States sits in a wheelchair commode, speaking in a synthesized voice. A man in a lab coat and rat ears stands at a screen designed to look like a cardboard box. A pulsating orb in the background has grown wings and disappeared, but not before encouraging the president to do a little dance. The entire company – the bare-chested redhead with wires in his hair, a Morgan Freeman-voiced man speaking through a basketball hoop, and more – emerge to sing about the ice cream man in a high falsetto.

“All of that?” the rat will say later, watching a head-on screen be cut apart by a digital red line, just one more insanity in a long line of surreal delusions. “Thank [the] acid brain.” We have seen first-hand how the mind will eat itself from the inside out.

“Symphony of Rats,” a mile-a-minute hysteria ostensibly following the president of the United States receiving messages from outer space, feels more like a semiotic hallucination. This kind of radical experimentation is characteristic of The Wooster Group, which premiered the original production of Richard Foreman’s show at the very same theater, The Performance Garage on Grand Street, in 1988. In this version, emphasis is less on plot and more on the emotional experience of madness in the postmodern technological era, represented right down to the conspicuous placement of mic packs and robotic voices.

Directors Elizabeth LeCompte and Kate Valk’s add a modern, technological layer reimagining of the Regan-era play, which premiered in a time without YouTube, much less the phrase ‘like and subscribe.’ When LeCompote and Valk asked Foreman if they could change the show, he responded “I hope it’s unrecognizable.” In its current direction, it’s hard to imagine this show set ten years ago, let alone in 1988. The characters reenact (in voice only) a superhero fight scene playing on the screen (named the ‘magic cabinet’) behind them. At one point this screen looks like the audience is playing a third-person video game as if we were the president, watching his virtual head move in time with his real one. While they signal from the very beginning that this 2024 revival is completely different from the original, it’s apparent. Within minutes of the show starting, we’ve already gotten an intimation that the entire play may have been caused by a dual COVID/flu booster.

In order for the show to work, the audience begins with a scene of the ‘president’ completely lucid, allowing us to trust him before we see him become prey to his delusions. At the start of the play, we are shown him as real as can be – as the actor instead of president. Ari Fliakos, as the president, is masterfully convincing. He speaks so fluently and with so many natural interruptions (‘uh,’ ‘i means’) in this opening soliloquy that it’s hard to tell if he is performing. Last night he had a fever dream, he tells us, just like the president in this play. “For real,” he promises.

This introduction ends with a meditation on the role of the narrator before devolving into a kind of robotic speech that becomes characteristic of the show. Often, featuring out-of-tune synthesized voices, it is hard to tell if performers are lip-syncing or speaking in real-time. The president/actor hybrid himself focuses on the idea of this narration – the narrator is someone who is outside the piece, “just like you” he says. This thread, which has the potential to be interesting, is mostly dropped until the last line of the show. This is, unfortunately, not unique in Symphony of Rats, where many of the show’s interesting one-off lines share the same fate. The play throws so many ideas at you that most of them disappear as quickly as they’re said.

The majority of the text prioritizes instinctive response to the ever-changing, ever-crazier images and sounds over a broadcasted message. At one point, a character takes a piece of excrement from under the president’s commode and places it on a plate. In a scene after, the others smell it, nodding approvingly. A woman in the ‘magic cabinet’ cardboard box/screen makes cookies with it, knocking the final product out of the virtual world and into the rat’s hand in a piece of sleight of hand. Audience members visibly shuddered when he took a bite. Graphic and visceral, do LeCompote and Valk want us to make something of this? Is shuddering enough?

The last five minutes, by contrast, create themes out of images, bringing back elements from throughout and earlier in the play. It was not until this final scene that it occurred to me – was our main character really the president? Or was that a delusion as much as everything else? It is one of the most basic hallucinations, a raving madman claiming he is a king. I realized, then, that we have been just as delusional as the president himself, complicit in the fever dream happening onstage. It’s a reading that the production invites, given its divergence from the 1988 production. In the ‘88, the president is wearing a suit – here, in contrast, Fliakos wears a threadbare tank top and bright yellow rain jacket. He never quite appears presidential. Political commentary in the original has been abandoned in favor of delving into the delusions, as we see that this is a story of a man, frantic and surreal, more than anything else. The suit is just something he could wear.

This kingly fantasy becomes literal in this final scene. Everything gets brought into focus, a pay-off for all of the threads the play has established. A cardboard ice cream cone that we saw earlier, dripping down the face of Jim Fletcher, as the rat, is back onstage. We hear Fletcher invoking all the animals, going two by two, reminiscent of an earlier animal conversation where he argued that it is “so much fun to be inarticulate.” When, finally, Fletcher places an actual crown on the president’s head, a cushy red wall on display as the background of the screen in front of him, the commode becomes throne, and prison, alike.

This is what the acid brain does.

Leave a Reply