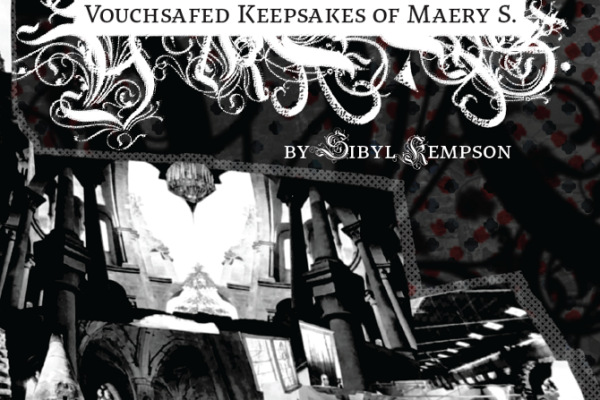

Long ago I fell so, so hard for Sibyl Kempson‘s elegantly wacky and uber smart plays– how they whip thoughts into dreamscapes, how their language is intuitive and chaotic and spiritual and playful. Kempson’s weird-ing of words makes new kinds of thinking possible. Her recent play, The Securely Conferred, Vouchsafed Keepsakes of Maery S. (out from 53rd State Press) is partially a treatment of the life of Mary Shelley & her step sisters, and of a monster (Bigfoot? yes and no?)—and Doris Duke, often riding a golf cart—or, no, all of these are only elements of a meditation on living the life of a writer. If you know Kempson’s work already, then you may guess that both the play, and our conversation here too, don’t take a linear path and find no conclusions or declarations—only questions, and a deep confusion that I trust and adore.

Darcie Dennigan: All of your plays are like magic mushrooms to me, so I was prepared, reading Maery, for my consciousness to unfold but ALSO—this play ended up being so emotional. I am like so emotional about this book.

Sibyl Kempson: It’s really emotional territory for me, too. I didn’t know it as I was writing it, but it is. Now I’m getting emotional, too, but it’s something about making, you know, making stuff and being a woman. Oh my God, it’s rough.

DD: Is it rough because it’s a midlife play? You’ve been making work for what, 20+ years? There’s something about how rambling the path is that Maery and the monster travel in this play—is it a crisis like Dante and his “midway through life, I found myself in a dark forest/ something something for I’d lost the straight path…”?

SK: I think we enter a lot of dark forests, not just in the middle of our life. Before puberty, it’s like, “I am who I am.” I am the most who I am. And then these little boobs start to come in and it’s so horrible. This isn’t what I thought it was going to be like at all, psychologically. And then your early twenties – nobody tells you about that– I had such a hard time then. And now. AND I think your 60s must be very tough, and that’s what the Potatoes was about (her 2008 play Potatoes of August that Kathy Ng recently directed in Providence, featuring two retired couples and several sentient potatoes)—kind of based off my mom & stepfather and dad & stepmother—there’s stuff that these people are clinging to, and they’re forced to let it go—

DD: I feel that all your plays are saying, “hey! guys! There’s something really wrong with empirical thinking.”

SK: That’s big for me. Because, okay, so my dad was a science teacher—

DD: No way.

SK: Yeah, an earth science teacher, and he is very, very cute, and my stepmother is a math person, my half sister teaches calculus, and you know I can’t, I’m a right brain. I always was tuned in a little too much, my antenna a little too sensitive, my whole life I’ve had a wild imagination that now goes more toward fear and paranoia. But I was really frightened all the time as a child, of stuff that nobody was talking about, or even seemed to notice. In the late seventies, a lot of creepy stuff was going on, UFO sightings, Bigfoot sightings, it was in the Zeitgeist. I would go over my dad’s and we would watch In Search of with Leonard Nimoy, which, if there is a more terrifying television show, I don’t know what it is. And then, my mom’s house was haunted and my mom would make a joke out of it so that I wouldn’t be scared… Oh, my God—I feel so crazy always saying this, but I think there are Bigfoots around the woods where I lived with my mom and all around where my dad lived. This is in New Jersey. I remember bringing my dad to show him this weird stuff that I found in the woods, and him saying, “Oh, that’s window sealant”—trying to come up with the perfectly reasonable scientific explanation. And so I’ve grown up not trusting science kind of at all because it never tells the whole story, it isn’t adding up.

DD: Your plays suggest that you have the ability to see and feel some things in the natural world, or just in the everyday world—sometimes invisible things—that empiricists and rationalists can’t…

SK: I think I do. I need to, too. I think I’m getting it back.

DD: Don’t know if I ever told you this but I went to see the Elevator Repair Service’s Fondly, Colette Richland. At the time I’m living in Providence, it’s complicated, I don’t really have any money to go to NYC and pay for a ticket. I’ve read Let Us Now Praise Susan Sontag & loved it, but I read lots of plays and don’t always drop everything and buy a ticket—anyway, I had this intuition: I needed to go. Oh my God! They’re eating dinner in their conscribed domestic nightmare but they can faintly hear ANOTHER play going on through the walls and then that little door opens up in their living room and ancient scrolls blow in… and I don’t know, everything was a-tremble with the thinness of the veil or something. But then midway through the play, these people in the row in front of me just up and leave! At first I’m like, what the hell, they’re so stupid and I’m not—but then after a while I thought, ugh I am probably way more like them than I want to be. So I watched that play with awe, and also with fear of my own narrowness, and also wonderment: how can Sibyl see these things?

SK: Oh! That play, half the audience was walking out during the previews, fully half the audience was walking out, and I was sobbing. But then half the audience would stay, and the half who stayed were really into it.

DD: In response to my emailing Jerry Lieblich that their awesome play The Barbarians reminded me of Fondly, they wrote back, “swoon!”—which pretty much sums up my experience of it too. I was in a full-time faint from that moment when April Mathis entered and said, “OH, HELLO. I didn’t realize that you had arrived. Perhaps you haven’t. Reality can be like that, whouldn’t you agree?”—You spread that wh diagraph all around the dialogue, and there was the old-timey 1930s radio show feel, really a whole soundscape– the feeling was… transporting.

SK: I felt the same. Yeah, the sound designer was my partner, we had been broken up for about a year when that play opened. But he was—did you ever meet my dog?

DD: Yes, he came with you to the library at UConn when you did the intuitive research/bibliomancy workshop—there was Rey, lying on the rug—I remember being so disconcerted and jazzed because—wait, you’re bringing a dog AND intuition into a university setting!? anyway—

SK: Okay that’s right. So he was my doggy daddy. We adopted Rey together. That’s what we did instead of having a kid. But he knew me really well, and he knew what I was trying to do, and he designed the sound, a beautiful job: Ben Williams—he really helped build this atmosphere. He knew what my atmospheres were, I guess. He is also a great actor and played Sailor Boy and The Krampus in that play.

DD: I think The Krampus is a precursor character to the Monster? There’s that line towards the end of Maery: “If somebody tells you that a woman is living a fulfilled life as an artist and also is living with a man, then that somebody is either lying or being lied to.”

SK: Kate Valk told me that. Years ago. And thank God. And then I had it proven to me over and over again. That’s the trick isn’t it? You can have a life as an artist but [dramatic voice] are you really fulfilled? But—I can’t get into it, because I turn into a monster when I’m really working. You don’t want to be around me. I can’t have normal relationships with people. That’s probably why I haven’t made anything for a while, because I found this wonderful sweet fellow, I’m living in his house in Central Florida, and I want to be a good person for him, and it’s not easy. Like for the 1st time. I want to be a good person. [slightly evil laugh? can’t tell] Whereas before I was always like, I just wanna make my work—and hiding in that, in workaholism.

DD: Well, I’m not sure what to say to that… um. Niceness is overrated? Or No, it’s just underrated by the patriarchy? Or it’s not an either/or? Or—I believe what you wrote in Maery more than I believe what you’re saying now? OK so you used the word monster—I don’t think you’re saying you turn into a monster like the “art monster” from that meh novel… I need to keep thinking about it, but obviously the monster is a character in your play– and yeah in one sense the monster is “a large angry male” but that’s just one piece—because Maery and the monster seem to be singular sometimes—and thinking about what you said earlier about getting boobs—and Maery’s line in the play about “all the terrible and dark experiences I underwent while growing through terrible and deadly femaledom”—Maery is also sort of a walking monster—

SK: I didn’t make the connection of the monster being also part of Maery. It’s not. It is. It’s also a version of her. That’s how I feel. Probably I’ll write about that next, somehow.

DD: I’m not really able to bring this point far enough, maybe in a straightforward interview, it’s impossible for me to adequately explain the idea of “monster” in your play? But definitely one way that your play upends any stupid binaries that the narrowness of our everyday language tries to create is by humor. Like when you’re talking about Helene Cixous, the “second-wave” feminist, Maery looks out at the river where she’s camping and sees the actual decapitated Cixous skull bobbing around in the waves –haha. Or in Potatoes, when the middle-aged women Bethy and Fern are arguing about whether events have meaning or are simply coincidence, before one side can win Fern says something like, “Shut up and cook the meal for the men”— which is such a funny moment and—

SK: I don’t sit down and say I’m going to write something that’s really funny. And with actors, if they’re thinking, let’s play up the humor in this play, no, there’s no intentional humor in there and if you try it’s gonna fall flat. They have to play it straight. There’s a line in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men where he’s describing one of the tenant farmers living in these destitute situations, and he describes the man making jokes, the kind of jokes that a man makes when he needs to self deprecate, and this man is actually harming himself in these jokes, you feel him harming himself for the sake of whoever he’s talking to. For me that’s definitely true.

Also with a lot of the stuff that I’m writing, I’m just trying to shoot it straight. And sometimes it’s straighter than how it goes in life. Because realist language—I never like it. I can’t conjure it in my imagination. Or in other plays where people finesse the language or have very sophisticated exchanges, no—I can only do the opposite of that. For instance, right now I’m listening to this audiobook by Ann Bronte. And I marvel at the way she can construct sentences to conceal or to let something show. I could never do that. I never know the right thing to say. I’m always saying the wrong thing. I’m always making the wrong gesture, sending the email at the wrong time. I ruin things again and again. I’m very, very clumsy that way. But in writing, I feel like that clumsiness is allowed. It’s a place where that is welcome.

DD: There’s also a momentum in your writing that everything gets subsumed by, and maybe partly why I find your plays so funny—the speed makes them so?

SK: Thank you for saying that. That’s important to me, and I’m not sure why.

DD: “I promise you that everything will go better when the entirety of ACT ONE is delivered in a sharp, very clear, and unnaturally fast-paced way. Leave no time for anyone to think—not the audience and certainly not the actors. There must be no pauses and a marked absence of any acting technique whatsoever —obviously that’s your stage note in Potatoes, and—

SK: It’s such a rude thing to say, too, like you’re just a vehicle for my words! But it does go better when you say the words fast.

DD: But look at your confidence there. Or for instance, in Maery your endnotes say, “I knew from almost the beginning of the project that Maery would not be played by a white woman…” There’s a confidence not necessarily in your self but in the work and your vision for it. Where did you get that confidence? Do you worry about the choices you make in your writing?

SK: I do worry. I worry all the time. But I will say, Mac Wellman is the one who gave me confidence by giving me so much permission. And egging me on. He just kept saying, “You are an important American playwright and it’s time to own up to that.” And it wasn’t to inflate me. It was to get me to stand up straight. I was not taking my writing seriously, and I never took myself seriously. He just kept at me. I would bring something to his playwriting workshop at Brooklyn College and he would say, “You have lost your mind.” He would look at me and say, “You’re a sick fuck. This is deeply disturbing.” You knew he was joking but also it was high praise to me. And he would dare me. Like once there was a poster for these two women doing a poetry reading at the college, the poster said, “bad girls, good writers” and Mac was like, “I dare you to write a play that’s called “Bad Girls, Good Writers.” [Aside—she did. TheatreMania describes it: “The story of two girls from the wrong side of the tracks trying to get their poetry heard. Wild parrots, a pervert spouting feminist theory, and the Baby Moses try to get in their way…”] Or I applied for New Dramatists over and over again. I kept getting rejected, I had applied for ten years, and that was it. I couldn’t try anymore. Then Mac Wellman called me, and said, Are you applying for New Dramatists? I’ll write you a letter.” And that was the year I got in. The confidence he gave me—it’s been a refuge for me.

DD: Maery—she’s so destitute in this play, there’s so much desperation. And facts from the life and times of Mary Shelley mix with more contemporary stuff, like when Maery says, “Yesterday I was reduced to stealing toilet paper from Moose & Sadies, and I got caught. I was like, ‘HOW?’ They were like, ‘we saw you do it on the security camera’ and I was like ‘you SECURITY CAMERA’D ME IN THE BATHROOM???’ Also: ‘What is a security camera’ and ‘I want a lawyer!’ But everyone knows I can’t afford a lawyer…”—The problems of making enough money to live are so palpable. I wonder if you are solving that problem in real life?

SK: Those moments of destitution are my own moments that I just wrote in. I read Muriel Sparks’ biography of Mary Shelley, where she talks of how desperate things would get for her in terms of money, even when Percy was still alive. And those money troubles are quite familiar to me. I’m writing the play and I’m trapped in Minneapolis. I don’t have any money in the bank. I’m on a residency, which is great, but I have no money. How am I gonna get food, stuff like that? For the record: it never did come down to stealing toilet paper from Moose & Sadie’s, but clearly the thought crossed my mind. And I was letting my imagination roll to worst case scenarios again and again, and then I thought I can plug this right into this play, this is part of the subject matter.

I shouldn’t assume that I have now figured it out. But I have just gotten a job. A job-job. A solid job, which is what I need because I’m over 50, I have no savings, I’m in debt. It’s scary. I need healthcare now, like I really need it. I was just going under and then this life preserver was thrown to me: I’m gonna be teaching at the University of Texas at Dallas, starting in the fall. Teaching acting and directing. But I’m not going to be teaching playwriting at all… I never made the wish to be in Dallas, Texas, but the more I think about it the more I think that it’s probably gonna be a good place for me in all these weird ways that I wouldn’t have expected. I was talking to my friend, writer Blaise Allysen Kearsley, and we were like, “Why are we so screwed?” When we were in school, working artists would come teach, then go back into the city and do their thing. They were freelancing. And they were fine. They were in their fifties, like I am now, and they were still freelancing, and they had an apartment, and they were fine! That was in the early nineties, and when we graduated, we all moved to Brooklyn. It was really hard for me right away, and it never stopped. I felt that the rents were always just like a little bit beyond what I was making at my little jobs. Lately I’ve been teaching at Brooklyn College, and living on my friend’s property upstate and taking the bus once a week and it’s okay, but I can’t do this forever. And I’m too old to be roommates with people. Inflation, gentrification, the television show Sex and the City, which was like the 3rd plague to hit NY… I mean there’s still plenty of people making magical, wonderful, amazing stuff. There’s scrappy stuff going on there. I don’t know how people are pulling it off, but they are. I just can’t afford it.

DD: I know you have a ton of community in the New York area, and that the writing and producing of a play sometimes go hand and hand for you. If you write another play, do you think you could produce it wherever you are? Or does it have to be in New York?

SK: No. I used to think so. But I don’t think that anymore. Florida and Texas. Those are my red states right now. You just don’t want to get pregnant, and I’m too old to get pregnant now, so I can live there. I’m safe as far as that goes. I think menstruation gives a certain experience of reality that I don’t see people who are not menstruating have. It’s several different kinds of insanity—or, what we would consider insanity in our society. I think a lot about hormones. You know how Carl Jung says that our psychology is what used to be mythology? And now I’m feeling that yes, that’s true, and our psychology is these hormones– they are what the ancients’ gods were like.

DD: One of my favorite parts in Maery is when Maery and Doris Duke watch a landscape painter at work in a field, and Maery looks up and thinks she sees the Monster out there in the field. And rather than looking harder at the actual landscape, she urges the landscape painter to go faster, so that via their painting, she can catch a better glimpse, and better see what she is seeing, better know what she thinks she knows… Is there some kind of art or literature or music that does for you what this landscape is doing for Maery—helping you figure out what you already know?

SK: It’s a little embarrassing, but I’ve been really into the Gothic novels lately – I can’t stop. And it’s kind of about my nervous system. I need them to be able to sleep. I tune into these epic Gothic novels and my own thoughts disappear. These are audio books that I’m listening to at night. I’m being read a story that is addressing the young, scared part of me. To me, what the Gothic always is—the Gothic is when there is mass death that is being denied by the ruling power. And then the Gothic addresses the deaths without addressing them directly. And we need that. I can’t be without it now. I need it to get through the day. And I’m listening to these books in my sleep, and the Gothic gets into my dream world. It really gets in there. And then in the daytime I’m remembering things I heard in the night. It’s like when you have a dream and it changes the way you go into that next day. I’m more receptive. And I’m embracing the darkness. It’s helping me to cope, somehow, and it’s helping me to move through the world in some different sensibility than what I otherwise have access to. The Gothic is disturbing. But in a way that’s addressing what is very dark on my behalf.

Leave a Reply