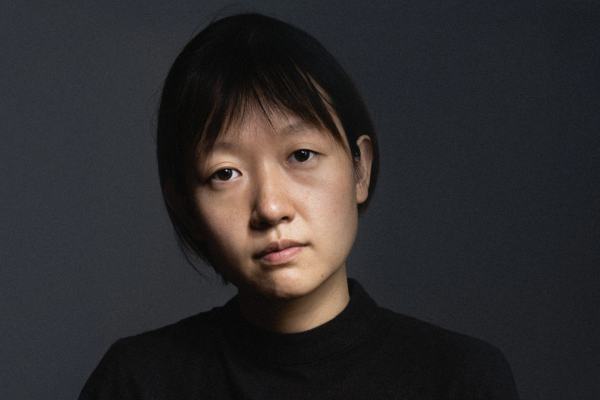

In Family (2013), a group of three half-siblings live together in their childhood home awashed with the traces of abuse withstood by their mothers at the hands of their father. One sibling is the product of an incestuous relationship, a dynamic she’s fated to replicate. In Endlings (2019), the story of three elderly haenyeos, South Korean female free-divers, becomes an agitated meta-theatrical meditation on narrative exploitation and the economic realities of creating art in New York City. Both pieces are entirely propulsive and land rapturously, even when read on the page. How can a filmmaker known for quiet, contemplative, and restrained films write such loud plays? When the opportunity to speak to Celine Song– in connection to the latest production of Family at La Mama this past September– became available (thanks to the ingenuity of a member of the cast), I welcomed it gladly. As a current MFA candidate at Song’s alma mater, many of my peers see Song’s career as epitomic, both for her bold style across disciplines and the seamlessness of her transition from theatre into film. This interview afforded me the opportunity to delve into her body of work, reading her plays as the origin of her artistic voice and then rewatching her films with fresh insights. Watching Past Lives for a second time, the uneasiness of Nora’s husband was particularly apparent. What at first seemed at odds– the quietude of her cinema and the brashness of her stage work– began to reveal a unifying project: one in which viewers are invited in to be wholly present to her work and delve into themselves, ultimately sitting with the anxiety the material might produce. The difference in timbre is ultimately less a matter of intention and more a function of medium. Look closely at Song’s work and consistency is wholly present.

I spoke with Song by phone last month, about the origins of Family, the distinctions between film and theatre, why a Starbucks should never serve as an entire film set, and her training at Columbia.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Eve Bromberg: I saw Family last night. Wow! Where did the idea of this play come from?

Celine Song: I wrote this play in 2013 for my thesis at Columbia. It was during a time where I was reckoning with the reality that there is no piece of land that hasn’t seen some kind of violence or genocide, even if the violence is only between two people. The play was inspired, specifically, by learning, as a relatively new New Yorker, that the area of Lower Manhattan, what would eventually become Wall Street, was used as graveyards for slaves. Since writing this play, we’ve started doing land acknowledgements to recognize that we are standing on genocidal land, but in 2013, this wasn’t common practice. The play asks how those of us who grew up in a violent place and were raised by violence and surrounded by violence at all times, can find peace and a new future? In Family, we meet these siblings and learn what their mothers went through at the hands of their father. After observing the siblings, you hope for them to try to come up with new structures and ways to be that are not so painful. And yet, we of course see them fail because they don’t have the language to change and reinvent the world in which they were born into. The whole play is about seeing the way in which they fail and will fail.

EB: I’m so struck by how different your plays are from your films.

CS: I don’t see them as that different. All my work comes from the same place and desires. I’m interested in the ways that the world is now and in creating something that is in some way brutal. I think that theatrical and cinematic forms have different purposes, but the intention of my work stays the same and will continue to stay the same into the future.

EB: Would it be fair to say that discomfort is a theme across all of your work?

CS: I wouldn’t say I’m interested in making people uncomfortable, it’s only going to make people uncomfortable if you’re already really fucking comfortable [laughs]. There’s a quote about this, about how art is supposed to disquiet the comforted and comfort the disturbed– [“Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.”]– the idea being that it really depends on who you are. What makes me feel a little weird about the word uncomfortable is that there are a ton of people in the world forced to live and contend with realities that may be labeled uncomfortable by other people but will feel quite comforted seeing their experiences depicted on stage. I’m interested in work that’s going to reveal something about the audience. In all my work, in my films and plays, the audience is never going to be told how to feel, but instead be asked to be alive– alert– to what’s happening. I want them to contend with what the work might uncover. Past Lives really asks viewers to question what they believe about destiny, about how history and time work, about marriage, about connecting in a world where there’s so much modernity. Some people were glad Hae Sung got in the Uber without Nora, and others wished Nora had left with him. Your response has to do with who you are as a person at that moment of viewing, but how you respond is also likely to change over time. When I wrote Family in 2013, everyone looked at me with such confusion about why I chose to write that play then, in the middle of the Obama years. But, people started to be interested in this play and once Trump became president. The truth about how the world is broken is always going to be true, but how we feel about it is going to change.

EB: Would revelation be more apt? Revelation, as an aim, is consistent across all your work?

CS: Yes. It’s an unfortunate reality that art is often meant for the social and economic elite. As a result, a play like Family is likely to make the majority of the audience uncomfortable. The problem with art is that it’s meant to be democratic. But, to see my play in New York, you need to be able to pay rent in New York. You need to be able to take your evening off. Not everybody gets to take the evening off. And there’s the cost of a ticket, which is pretty high, somewhere around 35 or 50 dollars. There has to be some level of economic security for you to come see this play, to even be in the room. Movies are more democratic. Right now, you can rent Materialists for less than $10. Maybe you have to pay more than that, but eventually it’s going to stream. It’ll always come back to who’s going to have access to a story. And then, how they felt about it. That’s what I’m interested in more than anything. I want people to show up and dive deeper into themselves.

EB: Could you speak a bit to how you see the difference between theatre and film as media?

CS: They’re very different. I’m not interested in writing a sitcom for a play or in trying to do something theatrical for movies. The way these two forms are encountered by the audience is also completely different, so they need to be written differently. While character, story, arc, narrative components exist across the media, how the stories get told comes down to the relationship between time and space. In theatre, time and space is quite figurative. While in film, it is very literal. This means that the stories will move differently. If you age somebody by 20 years in film, you’re going to alter the character via hair or makeup, or costume. You might even add a slug line. But in theatre, you don’t have to do anything. A person can sit there and age themselves through language and the audience will go along with them through decades of time. That is the most amazing thing about theatre. What really bores me is when theatrical potential is quashed by something so literal: for instance, in a play where a singular scene takes place at Starbucks and there’s a decision to make the entire set a Starbucks. In a film, you have to bring the characters and audience into a space, so you choose to shoot at a Starbucks. You find a good looking Starbucks and shoot there. But for a play, why are you building an entire Starbucks for a singular moment? It’s such a limited approach to what theatre can be. The power of theatre rests in characters sitting there and speaking. What an amazing, powerful thing. If a play takes place on Mars, you don’t need to build Mars! I mean, if you want to do something interesting, you can maybe put some red sand on the stage and then, you know, and maybe light a character in a particular way. You can make choices to alter things that are meant to be evoked, but it doesn’t have to be literal. What I don’t need is for us to build Starbucks on stage! It’s a waste! By speaking about what happened, the audience will all have experienced it. In the case of Family, we don’t need to see something a literal depiction of the abuse because we’ve imagined together what the siblings and their mothers have gone through. By them telling us, we know. This is theatre’s power and it must be protected. I’m so tired of walking into theaters and then just seeing a sitcom set. Why are you working on a sitcom set?

EB: For our last question, I’m curious, what was your training at Columbia like?

CS: The beliefs I have about time and space and theatre, about its purity and the worthiness of protection, are things I learned at Columbia. I was in classes with Anne Bogart and Chuck Mee, who were bastions of experimental theatre. Chuck and Anne taught us that every play written is a whole world unto itself that reveals the worldview of the playwright. A play is going to reveal everything about what the writer believes about the world. Do things happen randomly or logically? Is language articulated or is it blunt? Whatever your ideology is will be revealed through your work. There’s no such thing as apolitical or anti-ideological work. There will always be ideology. Chuck and Anne were both artists at a time where being political was not a nasty thing. Where being political was part of being an artist. You had to be. The work was meant to be anti institutional and anti corporate and exist outside of capitalism. They never shied away from an ideological alignment. There was fearlessness there. They were fearless.

Leave a Reply