The Builders Association: Shannon Jackson & Marianne Weems in Conversation

This book begins with the building of a house, and the building of a company while building the house. It expands to look at the ideas found in various rooms, some of which expanded into virtual space while they still were grounded in the lives of the artists in the house.

This book begins with the building of a house, and the building of a company while building the house. It expands to look at the ideas found in various rooms, some of which expanded into virtual space while they still were grounded in the lives of the artists in the house.

– From the preface by Marianne Weems

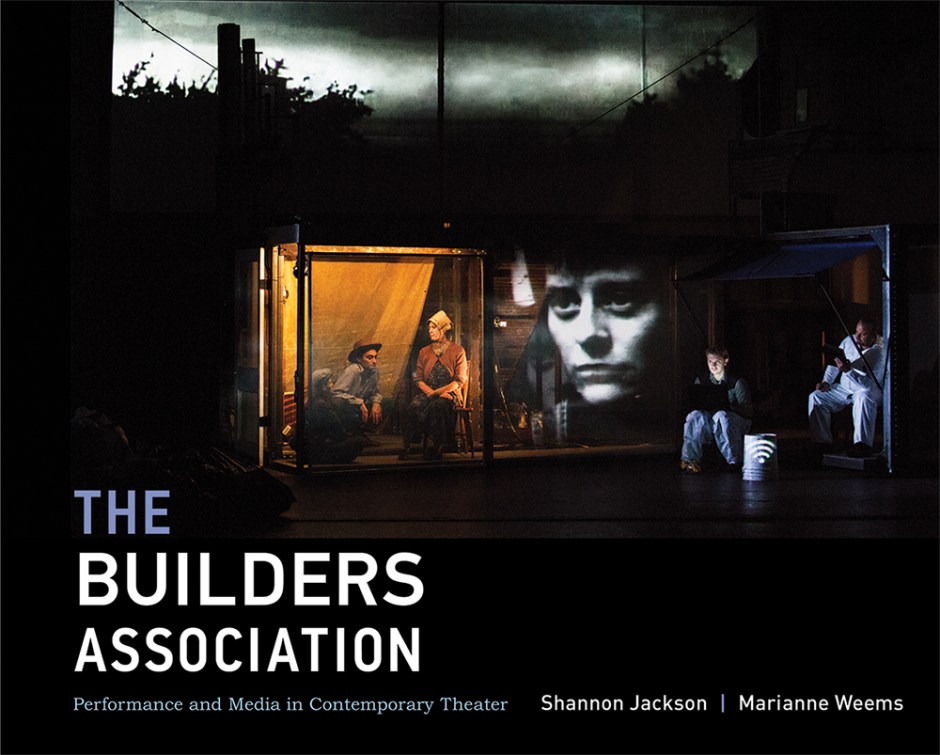

In their new book The Builders Association: Performance and Media in Contemporary Theater, performance scholar Shannon Jackson and Builders’ Artistic Director and Founder take readers through a history and analysis of the company’s life and work. The writers unpack individual pieces (MASTER BUILDER, IMPERIAL MOTEL, JUMPCUT, JET LAG, XTRAVAGANZA, ALLADEEN, SUPER VISION, CONTINUOUS CITY, HOUSE/DIVIDED) through an organizational rubric that evokes both a performance production timeline and a research process. As we go through the “Openings,” “R&D,” “Operating Systems,” “Storyboard,” “Rehearsal/Assembly,” and “Closings” of each project, aesthetic, conceptual, and practical revelations about “new media” theater and performance emerge.

Culturebot contributor Eva Peskin sat/Skyped with Weems and Jackson to discuss the book. Weems and Jackson will be panelists at Culturebot’s Scanning The Landscape discussion series at Under The Radar this Saturday, January 16th, at 12pm.

******************************************************************

EP: To start, I would love to hear more about the research process–it seemed like an excavation process–going through both the material and immaterial artifacts. Especially because I was so impressed that from a show from 1994 you have a cocktail napkin that has a budget for an after party–

SJ: Marianne! Somehow she kept those things. It was really lucky that there was actually so much paper archived, considering that they are a digital, media-based company. I felt really lucky that Marianne had been such an incredible archivist, also of things that were so symbolic of really important parts of a process, or interpersonal dynamics, or Aha! moments when something was going in one direction and it shifted into another direction. I really felt the material helped us see that. So then it was just hard to figure out what to put in the book, because there are so many other delicious things in those boxes.

MW: There’s a great part that you wrote early on about being surrounded by boxes, because I remember the kind of assault of just giving you all that material and thinking, “Oh well, she’ll figure it out…” And it’s a mountain of material.

EP: Where do you keep it all?

MW: We keep it in a storage unit. But now the book is done, it’s going to go to the Performing Arts Library.

EP: As a material artifact, or as a scan?

MW: No, the whole thing. All the boxes.

EP: Is there a thought to digitize things?

MW: Well that’s what they are supposed to do. I think it takes them years and years. Some day.

EP: Sure.

MW: Shannon, I was just remembering what a relief it was when we finally got to to SUPER/VISION, because that was when mostly everything was digitized. And I was just like, “Oh my god, I don’t have to find that article, it’s right here!” But also we had just gone through the process with each chapter so many times, so by the time we got there, it was a little more clear what we were looking for. But the fact that it was already digitized was huge for me, in terms of just making sense of the material.

SJ: Right!

EP: I did like, though, that in the Introduction you have this analogue of the boxes and the windows, and how it’s just as overwhelming to sift through digital archives as it is physical ones.

******************************************************************

EP: How did you come to the operating system of the book itself? Was it a conscious choice in the beginning to go through each project? Because the chapters, to me, are structured like a production timeline. Was that a launching point, or did you come to that later on in the process?

MW: I think that we conceived of that almost immediately. Shannon came up with the structure within each chapter, which I think was key. That’s really what coheres those various productions. Do you want to talk about that?

SJ: Yeah. I think that it was partly categories that came up responding to their process of assembly, and also clarifying–to some degree mapping to a conventional theater production process, but also exposing all the places where that process changes and is different because they are such a research-based performing arts company, and because they are a new media performing arts company. Traditional categories of theater-making got undone and re-defined, and so we were looking for words that resonated with that double-aspect. This is theater in the making, but this is also new media research in the making.

MW: I think that was particularly true for “Operating Systems.” I mentioned it in the prologue, and then you do in the introduction. And it’s such a key part of Shannon’s scholarship in terms of supporting systems. But also, it was just so satisfying because it was about the building–literally the underpinnings of administration of the fucking thing, and the conceptual construction of the project, and they both are systems. So that was always really gratifying to come back to that.

SJ: And that the systems are not ancillary, backstage things you wish you didn’t have to deal with, but that they are part of the aesthetic process–integral to the aesthetic event.

EP: I had a question about that, and I’m a little hesitant about asking this. There’s so much about the process of making these works, and in the same way that the work foregrounds the systems that are making it–and maybe this is just where I am in my own work–but I was so curious about funding for your work, and I’m sure things were really different from your first project to your most recent project. But I would have been so interested to see where money came from to make all these projects, because there’s a lot of talk about the non-profit laborer, and these invisible support systems. I wondered if there was a conscious decision not to include that information–if that is a whole separate project–or if that just didn’t seem interesting to you guys?

MW: Well, I think there was a point where we were going to put the grants in the End Notes of each chapter–and there is also an indication of co-producers, and that’s really where the money came from. I mean, it’s true. We, very briefly, talked about including a budget.

SJ: It was on a short list for possible documents, in the cocktail napkin mode. But I think, in looking at some of them, part of it is that you’re disclosing stuff about other institutions that we would have, I think, had to ask permission to disclose. And also disclosing things about people’s salaries. It’s a huge thing. I am really interested in that issue, actually, Eva–thinking and talking really frankly and overtly about money. And in my own work over here in Berkeley, we’ve been doing things where we try to do that, and it is hard to do.

EP: Is it?

SJ: It’s hard to get people–artists, and curators, and institutions–to frankly talk about money. And I think it is another project, and it kind of needed to be its own project, and needed to be about getting the permissions. And the vulnerability of artists or institutions, that they might feel at that time, we would have to work that all out. I think it’s a really interesting question, and it’s a really important topic, but it’s its own topic.

MW: But I feel that I tried to address it right at the top, in terms of people saying “How much did it cost?” Because that was always something that tagged us everywhere. And if people realized how little we worked for, and how much we stretched every single penny, it’s absurd. So then you get into, “We did it for this amount, and we should have had that amount,” and it’s so complicated.

SJ: I think that we do talk about it, even if we are not saying the numbers. SUPER/VISION was a big example of exactly that. And it is sort of this interesting thing, where there is an aesthetic that looks more expensive than it is, you know?

EP: That came up in the ALLADEEN chapter a lot. That’s what made me think about it–I think there’s some quote from Jennifer Parker-Starbuck about how the slick visuals put a mask over the fact that it’s actually enacting capitalism, but–I know from the inside of making work like that–that does not feel like what’s happening at all.

SJ: It’s an interesting point, because perhaps you could say it’s the occupational hazard of working in “new media theater,” or also trying as much as possible (as the Builders are always trying to do) to be responding to whatever latest technologies are on the rise and affecting our lives socially. And that with the decision to do that, you end up getting enmeshed in things that look expensive, even if they’re not.

MW: But not intentionally, as we express many times. It is the critical frame to use that, and try to use that seamlessly. That was the idea in that show, and a lot of the subsequent ones. I think we began to judge how many fissures we could show, but certainly that show was about seamlessness.

EP: I think it gets at how we imaginatively value art, and how that translates to actual capital. I read something recently that people have some perception that the NEA gets like, 1% of the national budget, when it gets like, 0.0000005% or something. So there’s a huge disparity between what people imagine value translates to in art-making and then what that actually means in terms of money.

SJ: It’s a huge thing. I think it’s really its own topic. We’ve done some symposia and some publications here at Berkeley around the issue, and also, interestingly, trying to join efforts to talk about money in the visual arts in relationship to the performing arts, because there we have different models colliding. And, again, we had so many goals in the book–to track the emergence of an aesthetic, and also all of the different issues technologically and socially that the different pieces address–but, I do just want to say that I think this is a great type of topic for something like APAP or Under The Radar, to figure out how to talk deeply, and non-defensively in relationship to many, many other groups (I’ve been involved with WAGE, and others) and to many other attempts to have the conversation about money. And I think that whether it’s the NEA, or people’s assumptions about how much visual artists make versus performing artist, or assumptions what the artist should bear herself versus what the institution should bear, all of those are really interesting issues. And we won’t be able to address them until we’re ready to surface them all together.

EP: Well, getting back to the book, could you talk through some of your original goals, and how those goals might have evolved over the process of working on it?

MW: I have to say, I came across our book proposal structure, and it’s remarkably close to the product! I can remember, we sat in this very living room and did a sample chapter. We did MASTER/BUILDER. And it was really–not the writing, but the structure and the visuals were almost exactly what ended up being in the book. So, I think once we came to that structure, we didn’t have to throw it aside in the process of making the book.

EP: You mean the structure of processing through projects based on the organizational system Opening, R&D, etc.?

MW: And also just using the productions as chapter markers.

SJ: It could have been that the breakdown of the chapters were thematic, but the show-by-show structure was clear. And also, in terms of thinking about goals of the book that ended up staying, one of the goals is to show how much each production responds to a different technological moment. In part, to show that when we talk about “new media theater,” or art and technology, that there are really different ideas, and sub-themes, and political themes that undergird different facets of that combination. I felt that each show took on a different nexus. There were so many differences across the shows, based on the technologies or the issues that they were addressing. And that was a goal, too, to show that relationship–in part, to show how much from 1992-94 to now things have already changed in that time. Think about what a surprise and shock it was, actually, for so many Westerners to learn about the call-center system, which now has popular cultural TV shows on it. Or even some of the shock, when we were working earlier, about how our students at Berkeley use (used) Facebook.

MW: It’s true!

SJ: Now, it’s so standardized and normalized. Noticing all that projection, and those pivot points in the recent history of technology–showing that inside of the book was a real goal.

******************************************************************

EP: I wondered if you had a perception of the book itself as being a kind of Builders’ project? It does feel like you go through the same kind of research process–

SJ: It’s the only show I get to be part of!

MW: Well, there’s always the next show Shannon!

SJ: I’ll act for cheap!

EP: Because I loved the concept of the “distribution of sensibilities” that comes back throughout the book, and I was wondering how you (Shannon), working in scholarship and academia, and you (Marianne), working in live performance, situate this book project within those landscapes.

MW: I certainly think that Shannon has some background in live performance, and that was kind of a moment of trust, or bridge-building or something, because I knew that Shannon actually understood what it took to make a show. So there was that basic lingua-franca. But also, we engaged in a process that, almost immediately, felt so familiar to me in terms of “making the shows.” You get the idea, and then it takes years to drive it and turn it into the production.

SJ: I think, from my end, what is familiar and different in creating this kind of book, I would say the process of assembly (which is so much part of [The Builders’] aesthetic) really felt like a way of defining what the book is, more than other things that I’ve written before. And so that sense of holding several things, and re-ordering, and re-framing, and trying this first versus second–I thought that was a very big part of the book. Also, for me, two other things that were really different: one is that the visuals–images of the performances and also the documentation–are an essential part of the argument of the book, in a way that my previous publications haven’t been. And so in the final assembly, it became a bit more of a delicate and different act for us to think about the relationship between text I wrote and image that’s there, and what was going to reinforce versus what was going to be redundant. That whole sense of it being a text-image assembly artifact was newer for me, and exciting for me. Another thing was that I guess I’ve written one book on one institution before, but usually I do work on certain projects of certain artists or artist groups, and I don’t think I’ve ever done something where I got to see the work of a group unfold, and be responsible for writing about that unfolding. That was new for me.

EP: And do you have a sense of this book having a different life versus previous works that you’ve published? Is this particular publication moving in a different direction in terms of where you want people to be reading it, who you want to be reading it? Is there a process that you go through after you’ve made an academic book of sending it to people to get it to be part of the field, and is this work different?

MW: Well, MIT has a distribution network that they are trying to deploy, so their catalogue is sent to all kinds of universities, primarily, so that market is pretty self-explanatory. The other one is really kind of a question mark, because, as Shannon said once, the book is almost too pretty to be an academic book.

EP: It’s almost like a coffee table book.

SJ: A pretty heavy coffee table book.

MW: The writing is much too smart!

EP: A coffee table book for geniuses.

MW: Yeah, exactly.

EP: More than in terms of buying it, who do you want the readership to be?

SJ: The ideal would be to be doing bridge-building among different sectors–those who understand themselves to be working in interactive media versus those who understand themselves to be working in theater, versus those also work in video installation or in choreography, or in the visual art world or in the architectural world. The Builders’ aesthetic is drawing from so many different forms, they are a convergent point for so many different types of creativity. And if we could find those readers so that they could also find each other, that would be wonderful.

EP: And so, two-part question: did the writing of this book lead to the Builders’ archives being sent to the New York Public Library, and is there maybe another, unfolding life that is starting from this book and moving outward. Could this lead to a companion piece online? Or is there some way this book relates to these archives, using the library as a point of access?

SJ: As a professor, I would hope that that would be the case. And for a while, before anything like the Performing Arts Library came on, we wondered about trying to create some kind of online archive. That would have been hard! And expensive. But the ideal would have been to create a more expanded thing on the Builders’ website–that perhaps you bought the book and had access to more. And now, I think this is the right relationship between an institution and the Builders, to have the Performing Arts Library graciously take on this. There are so many more things to explore in their work, or in the issues that they were addressing, that I hope there can be a nice synergy between the book and the archive, and that many people will write and research many more things.

******************************************************************

EP: The way that the analysis is integrated in the history–it’s not organized conceptually in terms of, “here are the themes that, as a scholar, I have pointed out, or picked out”–those things emerge throughout the analysis of each work. I thought that was not like a lot of other books that I’ve read.

SJ: Yeah, it’s not like other things that I’ve written. It’s more the monograph on an artist, you know? Which is, perhaps, a bit more common in the visual art world, it isn’t quite as common in the performing arts. And at the same time, we were inspired by other books that were doing this, actually. We were looking at books that had come out at the time around The Wooster Group, or around Goat Island, where it turned out that there were a lot of things you could learn by focusing on one group across many themes. It’s sort of like, putting together a writing project or a research project, what’s your manipulated and what’s your un-manipulated variable? And there’s a really useful thing about the un-manipulated variable of having one artistic group, albeit one that changes and morphs over time, provide the through line for the project, so then you can ask a lot of other questions along the way.

MW: I also think because Shannon’s breadth is so wide, it was so wonderful to see how you would clearly describe the thematic. Like in JET LAG–she wrote this beautiful thing about place and placelessness and compressing geography. All the things that are inherent in the show were really explicated so gorgeously. Also with HOUSE/DIVIDED, she went to this completely different place, which was the Washington Federal Arts Project?

SJ: The Federal Theatre Project-

MW: And that was something I had never thought of, and was such a great accompaniment and duet with what was already in the performance.

SJ: It wasn’t hard to work out, but I needed to be clear that I was going be allowed to make my arguments, even if they weren’t necessarily arguments that Marianne and the Builders team had in mind when they made a show. And I appreciate that you (Marianne) allowed me the latitude to do that, because I didn’t want to just be a documentarian–first they did this, then they did that–I wanted to be able to make some arguments.

MW: Well, it made the book really a book. It makes it so much more interesting, that it isn’t a monograph.

SJ: Anyway, some artists really wouldn’t like that, they wouldn’t appreciate that–like, “our issues were this, our themes were that, please write about those things.”

EP: I wondered about that–anytime you track through and nail down the many machinations that have gone into the making of a work it can have the effect of mythologizing the process, or making each work seem like this mythic event. And I was just blown away by the conceptual clarity of each piece. The processes, the stories, and themes that were coming together seemed so rich and I wondered if your understandings of your own work (Marianne) changed in the process of having Shannon analyze them. What was the back and forth there?

MW: Certainly with something like any of the shows–like SUPER/VISION, my original concept was that we should do something about dataveillance. So I did a ton of research and brought that to the group, and we created the stories, and it all kind of rolled out from that original seed. So that has been a coherent tracking mechanism throughout making the shows. But Shannon, obviously, amplified that in many different ways. One thing that I had completely overlooked, that Shannon has been instrumental about, is working with all these different media. Literally working with people in radically different genres and media. Putting that together always seemed like second nature, but now in retrospect, I see that some of those fits were unexpected at the time.

SJ: Yeah–unusual. Especially when we talk about collaboration across the arts, or misunderstanding and misrecognition across different art forms, I think it is really amazing how many different kinds of collaborators they had on hand. It seems like it did feel like reflex and habit and normal for you, but from another vantage point, it’s like, “wow!” Who knows that you have Kiki Smith making sculpture for theater? At least half of their projects seem to be about excavating earlier popular performance histories, or earlier media histories, and that was something that was completely unexpected to me. I think when I began the project I hadn’t quite realized how much of their “new” aesthetic is informed by and excavation of the old. That was huge for me. The revelation of all of that work, and all of that conceptual rigor, is a goal for me in the book. To make sure that people realize how much deep thinking and deep research has gone into the making of these works. Sometimes I think in performing arts we’re at a disadvantage because we have attendees just see that show, usually one time, in the space of an hour to an hour and a half (Builders shows are short), and that is it! And I hope that the book helps reveal layers and texture and labor that were a huge part of the making of the work, and also how much ideas are central to the making.

******************************************************************