“There he is.”

Nicky Paraiso is sitting next to me and wants me to look at something on his phone. Ostensibly, we´re here at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery to see a show, the first of Danspace Project´s 50th season, but tonight feels more like a reunion, a gathering of old friends. It’s 7:15, the event was meant to start fifteen minutes ago, but nobody seems to mind waiting, idling. Ishamel Houston-Jones and KJ Holmes are chatting on the floor in front of me. Behind me in chairs are Cynthia Hedstrom and Carol Mullins. To my right is Bill Young, and to my left Yoshiko Chuma. The audience contains multiple generations of New York´s “downtown scene”, an extended family of long-time friends and colleagues coming together in an almost festive atmosphere.

“There´s the man,” Nicky said.

I look at Nicky’s phone. The picture is black-and-white, one I have seen before. I think it was taken sometime in the 1980s. The camera catches a dancer in mid-motion. But, even in its stillness, the viewer can detect the dense fluidity of this dancer’s body, as if his flesh were made from mercury. Looking over one shoulder directly towards the camera, his limbs bend in a complex array of energy; his expression is both serious and also bemused at the idea of his movement being captured and immortalized. His face exudes the calm of a scientist engrossed in an experiment. Or maybe more like the statues of Buddha I saw in Japan: a firm but faint smile, the production of the detachment of observing sensation. Given the subject, and the unusual art he created for more than sixty years, it is probably a bit of both.

“Yep,” I reply. “They don’t make ’em like that anymore.”

Steve Paxton is perhaps most famous for instigating Contact Improvisation more than 50 years ago, a simple improvisational structure where two bodies share weight and touch. Despite its popularity throughout the world, from dance education settings to performance contexts, Steve remarkably never sought to trademark Contact or be the one to exclusively “own it”. He wanted CI to live in the world, to “open source” this form of movement experience so that anyone could practice it, similar to how John Cage hoped to allow more to participate in the creation of contemporary music. By allowing Contact to “go viral,” more people could begin to explore and develop it without needing to jump through the hoops of a formalized educational setting. No one is “certified” in Contact Improvisation. The dance is shared between all of us.

I remember him saying once he wanted Contact to be similar to teaching someone a card game: the rules should be simple enough to explain how to do it quickly, so you could get to playing as soon as possible. Such a simple idea, yet so radical at the same time.

I only met Steve Paxton twice, and never had the opportunity to directly study with him. And yet, I feel his influence in my life over more than three decades has been both central and profound. I was first introduced to Contact Improvisation in 1992 while studying with Paul Langland at the Experimental Theatre Wing at NYU, and later studied with other Contacters Danny Lepkoff, Kirstie Simson, and Nancy Stark Smith. When I was an undergraduate studying with Nina Martin, to provide intellectual context, she screened Fall After Newton for our class. Mary Overlie encouraged me to get a subscription to Contact Quarterly, a magazine started by Nelson and Smith to provide a snapshot of the Contact Improvisation community through photographs, interviews, and articles. Contact Quarterly also included written pieces about related disciplines, such as Bonnie Cohen´s Body-Mind Centering. Living in the East Village in the 90s, my friends and I went to Open Movement at PS 122 regularly, as well as performances at Judson Church. More and more, connections were being made in my mind between what I was learning and what I was seeing. It was an incredibly fertile and exciting time to be in New York.

By forging an artistic vocabulary out of standing, walking, leaning, and rolling, Steve created an environment in which anyone could be a dancer, or reminded us that everyone already was a dancer.

Steve didn’t live in New York during those formative years when I was discovering my voice as a mover. And yet his presence seemed to hover over Lower Manhattan. Unlike other dance artists at the time, who organized giant productions and tours, and played on huge stages with large casts, Steve was more spare. He did solos, infrequently, at small intimate venues. He enjoyed global fame and respect while remaining reclusive; he seemed wary of the spotlight, of the whole business machine of the arts. He was not a guru, but seemed to live the life of one: he occasionally came down to the city from his farm in Vermont to teach a workshop or do a handful of performances before disappearing again. Steve was magnetic and mysterious, and utterly different from so many of his contemporaries.

But how does one capture the legacy of an artist whose work is frequently associated with improvisation and spontaneity? Thankfully, because film became increasingly portable and affordable starting in the early ´70s, there is an extraordinary collection of rehearsals, workshops, interviews of Steve and his work spanning more than half a century. Organized by Lisa Nelson and Cathy Weis, two long-time collaborators, Steve Paxton – a video amble is not a performance yet is much more than a mere video screening. Hosted nearly one year to the day of Steve’s passing on February 20, 2024, in a church where he performed numerous times during his extensive career, and attended by so many people who knew him for much of those decades, Steve Paxton – a video amble was a celebration of life.

After digging through hundreds of tapes across multiple media forms over the winter, Cathy and Lisa opted to create a mosaic versus a singular definitive portrait. Over approximately 45 minutes, the resulting film retains the contradictions, humor, wisdom, and beauty of Steve as both an artist and a human, unfolding at a leisurely pace. “Amble”–to move at a relaxed and slow pace, especially for pleasure–proved the perfect lens through which to frame their goal.

Some segments of Steve Paxton – a video amble are what one might expect in an evening commemorating the legacy of a highly influential dance artist of the post-modern era. We saw some of Jim Mayer´s beautiful footage from Fall After Newton (1987). Does anyone ever tire of watching Steve and Nancy Stark Smith doing Contact Improvisation together? There were also excerpts from Some English Suites (1993), an exquisite solo of Steve I can recall seeing for the first time at Danspace in 1999. There’s a passage from PA RT, where Lisa appears to be wearing a mustache while Steve wears sunglasses, both moving to a haunting score by Robert Ashley.

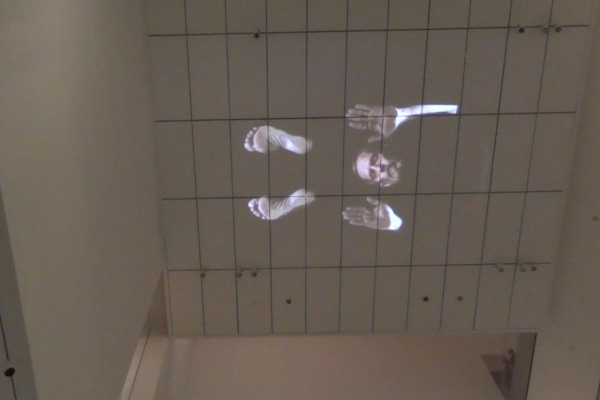

There is an excerpt from his performance/installation piece Beautiful Lecture/Air (1973), which invited audiences to choose between watching a recording of Swan Lake, a pornographic film, or a live broadcast from then-President Nixon. Another snippet was from Physical Things (1966), a collaboration between Steve and engineers from the Bell Laboratory where audiences were able to traverse a landscape of giant plastic tunnels. Another, filmed in collaboration with Cathy in 1991, featured a tree in Vermont whose roots were so exposed that the ground around the base of the trunk created a see-saw effect: Steve jumped, leaned, reached, and interacted with it. Equally as powerful are the home movies, such as Cathy filming Steve kayaking down the Clyde River in 2017. Or Lisa´s first film collaboration with Steve from 1985, where she records him maneuvering a tiny plastic foot on a string across a piece of flypaper.

Lisa and Cathy resisted video amble unfolding chronologically. By roving back and forth across time, toggling between urban and rural settings, alternating between improvisations and more “fixed” pieces, interspersed with Steve talking about his work or simply working on his farm, Steve Paxton – a video amble accumulates greater meaning and potency as the film unspools. “The media we make now will become a memory in the future,” he observes at one point. In another clip, he affirms that “the real medium of my work is gravity”. As a teacher, he remained endlessly enthused at how “many principles there are in the body,” which move “at the speed of action” during a performance. Somehow, hearing the founder of Contact Improvisation say, “I doubt anyone can really teach you how to improvise” just feels right. It makes sense. Each moment in the film feels self-contained and episodic, without ever feeling confusing or chaotic. All of it connected to some ineffable larger whole, a trace of Steve’s mind. His method.

When video amble finished, I wondered how this event would be interpreted by someone who knew nothing about Steve or his work, who did not share any personal history with him or his ideas. What would they take from this idiosyncratic array of excerpts? What would they make of this evening? Do the ideas and explorations posed within his art remain compelling for people today? Or would a stranger just think this a curious time capsule about an eccentric man from a different era?

Judy Hussie-Taylor, the Artistic Director of Danspace, said that this year’s season was inspired by something Steve wrote to her in an email from 2012: the “the work is never done, and sanctuary is always needed” (a sentiment which feels even more urgent today). After the amble, she invited audience members to ask questions or “share any memories of Steve.” A young person in the audience asked if Steve was right, that “improvisation cannot be taught” . An older person said that they remember seeing Beautiful Lecture / Air when it premiered at the 14th Street Gallery in 1973, and that they didn´t know how to decipher it– that this was often the pleasure of encountering Steve´s work, the “not-knowingness”, the “unknowingness” about it.

Then Yvonne Rainer stood up. 90 years old and strong as steel, she first met Steve in the early ´60s when they were both studying with Robert Dunn (their classmates included Simone Forti, Trisha Brown, David Gordon, Lucinda Childs, and Meredith Monk–talk about a workshop!). Holding the mic in front of her like a torch, Yvonne quietly talked about how Steve was never that forthcoming about himself or his psychology in his work, yet was always fully engaged with the people he was talking to or working with.

“He was, by far,” she said, “one of the most unusual people I ever met.”

Yes, he was. Yes he is. They don’t make ´em like that anymore.

Thank you, Steve.

Steve Paxton -a video amble, Organized and Hosted by Lisa Nelson and Cathy Weis at Danspace Project at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery.

Leave a Reply