The Reactions and Theatricals of Caitlin Saylor Stephens

I remember distinctly in the spring of 2012, being on staff at The Lark and printing out When We Went Electronic by Caitlin Saylor Stephens, then sneaking up to the 5th floor lobby to read it (during working hours). And while that was an early version of the play that is world-premiering on October 27th at The Tank, Caitlin’s arresting voice and vibrant theatricality knocked me back as one of those talents one feels lucky to have happened upon.

Since then, I have followed Caitlin’s work closely as she’s held strong to her fearlessly poetic take on female violation, our infected health industry, toxic bro culture, and so many other issues, including mortality as seen through the lens of the Hudson River. As such, I am beyond ecstatic to finally see When We Went Electronic onstage and to have had a chance to interview Caitlin both about the show and her writing.

What first struck me about your voice was how viscerally you want audiences to experience your worlds. Can you talk about what sort of theatrical landscapes are you are creating?

I love building theatrical worlds that look, sound, and feel like a bad remix. You recognize them, but something feels over-produced and pixilated. Worlds that are hungover, trippy, psycho, dirty, nasty, and sweaty.

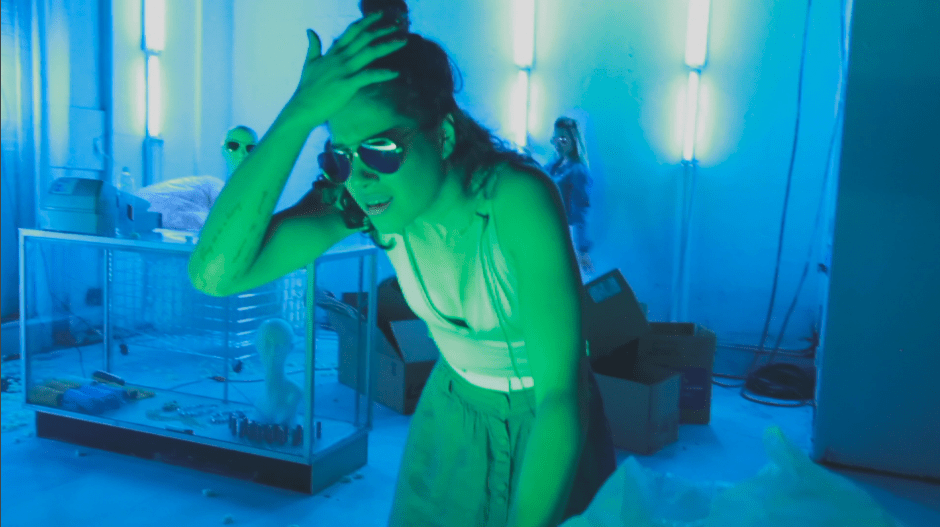

In terms of storytelling, I’m always moving towards a gut punch. Especially with Electronic, I want the audience to feel like they are on drugs and watching someone be on drugs or drugged. I want them (the audience) to be active participants in the problem. One unique aspect of Electronic is the hypersexuality of the world. The characters are American Apparel models and I wanted to evoke that golden era when their billboards were smattered at every major intersection in the city. Because the play is about rape, it was really important to explore the characters’ sexuality as a vehicle for self-agency and simultaneously make the audience culpable. I don’t want to let anyone off the hook. Even myself.

In order to achieve that kind of accountability, we built a world where the ‘sexuality bass’ is turnt so high that it has the potential to rattle bones.

I’ve always admired your embracing of other artistic mediums in your work. Why is that important to you? What other artforms and artists inform your work?

I was raised by writers and spent a lot of my childhood being dragged around to art galleries to see the work of Rothko, Serra, and Abramovich. I hated going to see art until I saw Dan Flavin’s work at PS1. Who doesn’t love neon lights? They mesmerized me and still do. Flavin’s lights have been in the Electronic script since its inception and are now an important storytelling device throughout the play. It’s strange to think that my most formative experience with art as a child is now the centerpiece of my play about sexual violence. Lighting design felt like the perfect way to express traumatic flashbacks and addictive impulsive reactive behavior triggered by trauma during the reign of American Apparel.

Sarah Johnston, our incredible lighting designer is tricking out this play with the most unbelievable fluorescents. We’re in tech right now and I’m just so excited to see this play glowing.

Beyond Flavin, my stepmom once took me to a holiday party at Cindy Sherman’s house. Ever since I saw her wigs hanging up in her studio at that party, I’ve loved her work. I identify with Sherman’s femininity and how she uses self-fetishization as a device. For a long time, I thought of Electronic as a satirized self-portrait because it is so deeply personal. Building a world of hyper-femininity was my way into that.

For Electronic, I also had a very specific style of performance in mind and used Ryan Trecartin’s A Family Finds Entertainment as a reference. Over the years, it’s been really hard to get the style of performance nailed down. But I think we finally figured it out. People think rape play and they move towards sincerity. But in Electronic it is so important to resist sincerity in order to reveal the painful truth. Meghan Finn, the play’s genius director, cited slippage early in our process. We talked a lot about what that means performatively, as well as politically, through the lens of gender and how that might manifest in the performance of this play.

Sarah Cagianese’s gorgeous electro-pop tunes have been a part of the piece for a long time. It was important to me to build many tonal layers, but also create a depth to the characters despite the vapid, existential, hellhole of retail where they exist. I probably would have given up a long time ago on the project if it wasn’t for the collaboration I had with Sarah. Embracing other mediums was completely essential to the life of this play.

You’ve always been a writer to me who is unafraid to step into disturbing, tense, and discomforting material, but your approach or lens is always unexpected and lets us examine these topics in ways we never would have. What draws you to these sorts of stories, why do you feel they are important to put onstage?

Life is triggering. I am triggered constantly. You either choose to run away from that reality, be victimized by it, or lean into it by accepting the truth of your own experience. My work is intentionally triggering because I want people to accept their truth, as painful, dark, or disturbing as it might be. I want them to ultimately heal. I want there to be progress. I am deeply fascinated by the source of pain and so any story that contains physical or emotional pain is something I want to explore and see on stage.

When We Went Electronic always stuck with me because it was at times uncomfortably funny, haunting, beautiful, and an experience. Having lived with this piece for so long, developed it so many places, how has it changed for you and what is it now going into production?

The play changed a ton during our process. Meghan is so punk rock, yet simultaneously an expert technician. Despite having workshopped this piece for six years, I really only learned what this piece was in the last few weeks after working with Meghan. She has this amazing ability to look at the devices you’ve built in and help you articulate the rules clearly. She takes every piece of evidence you drop and goes full-on forensic with it. But in a natural way that gives the writer room to write.

Meghan also facilitated a safe rehearsal room where we could all openly talk about trauma and sexuality so we could all take big risks and fuck up from time to time. The fact that she gave me the space to experiment just feels like, god, what a rare gift. She is a true artist and is not afraid of provocative, weird, or freaky. I’m totally obsessed with her.

As far as the writing, being more economical with the language was super important to me. I cut about 80% of the draft that had been sitting in a drawer for a few years. During our process, I discovered that the characters poetry was different than my own. They see a tagging gun as an artifact of beauty and I wanted to honor their experience by giving them a vocabulary that reflects what they view as important. For so long, I ran around with a version of this play where the characters spoke with my poetry. I finally realized I had to make a distinction. There’s nothing wrong with dirty or dumb poetry. Literally.

The language in your plays is often poetic, but also darkly hilarious, raw and vulnerable. How do you construct your language, what is your process?

That is very lovely of you to say, but I’ll be honest, I’m done with poetry. Look at the world. It is not poetic. Neither is the person sitting next to you on the train blasting viral videos at full volume. I don’t consider poetry a language so much as an examination of contradictions that happen around us. I recently shot a video for my side project @discounttherapyclub at Rockaway Beach about Isis execution videos. In the background, you could hear two girls discussing the last episode of “The Bachelor” while I ate a mango icee in a bikini and contemplated how the government retroactively attempted to save James Foley two days after his murder. What a weird combo of low and high, political and pop. As I staged that video with nothing except my body and my camera, I started realizing that the less poetic I am in the language I use, the more room it leaves for poetry in story.

Do you consider your work reactionary? Either to the world we live in, or to the types of plays being written about certain topics.

If I wasn’t so obsessed with dialogue I would probably get a neck tattoo and become an electro hardcore witch musician. The theater is so vanilla and academic and in the decade-plus I’ve been a playwright in NYC, I’ve never felt like I fit in. But feeling like the uncouth outcast is part of what I love about it! The vanilla-ness of the American Theater gives me something to fight against. Same with it’s out of control sexism. Deep down I’m a very tender person, but my work is full of rage. And I feel like the bad girl smoking in the parking lot next to most of my peers. I’m definitely not one of those hippy, earth-mama types whose career is exploding. I think I did drugs in every bathroom of the Lower East Side in my early 20s. That badness only gives me permission to keep edging and really pushing against what everyone else is doing. I love arguing. At the end of the day, I’m really looking to have a passionate argument with my audience. I want people to feel extreme feelings and yell at the stage! Yes. My work is extremely reactionary to both the world and the American Theater. Justice is my muse. I hope my therapist doesn’t read this. Or maybe…I do.

When We Went Electronic by Caitlin Saylor Stephens, directed by Meghan Finn, with original songs by Sarah Frances Cagianese & Caitlin Saylor Stephens, produced by The TANK, plays October 25 – November 11th (312 West 36th Street / First Floor / NYC 10018). For tickets and information: www.thetanknyc.org/theater/1280-when-we-went-electronic.