There’s a thing that theater does that is really important and kind of awesome.

The Following Evening does it really well.

It is going to take me some time to explain.

Or maybe not explain, rather, hopefully, show.

Before I lived in Los Angeles I lived in New York.

Before I lived in New York, I wanted to live in New York.

Sitting in my room as a teenager in suburban Baltimore in the mid-1980s, reading books and poetry, listening to records, I conjured a jumbled-up vision of bohemian New York. Allen Ginsberg, The Velvet Underground, CBGB, The New York Dolls, Patti Smith – those are the easy signifiers, the shorthand, the gateway drugs to the real thing, the thing you have to live there to feel, to experience, to be.

In college I learned about The Open Theater. In a used bookstore somewhere I found A Book on the Open Theatre by Robert Pasolli, with all these grainy black and white photos of the experimental theater ensemble rehearsing and performing in NYC.

I moved to New York in 1995.

ABBY: And when I arrived in New York, I was not prepared for this parade of people who announced with great victory and also real sadness that the city was over, the party was gone and I had just missed it. But boy was it a party, they told me. Boy, was it ever.

So I cried for a few weeks because I thought I had missed the thing I had come to get.

But you stay because you wanted so badly to be here and you do something in it and it does something to you. And then, the following year, a new crop of people will arrive, new people who’ve come to find something they heard, or read about, or heard in a song, or saw on tv. And that city they came to find is already gone. And you’ll be the one to tell them

In August, I emailed Abby asking her for a copy of the script of The Following Evening. I’d been trying to write about the show since a few days after I saw it on February 17, 2024 but, well … life.

There were some things in the show that I couldn’t remember exactly. A few moments came clearly to mind but mostly it was the feeling of the show that stuck with me, sticks with me still. Specific words and moments, that’s a bit harder.

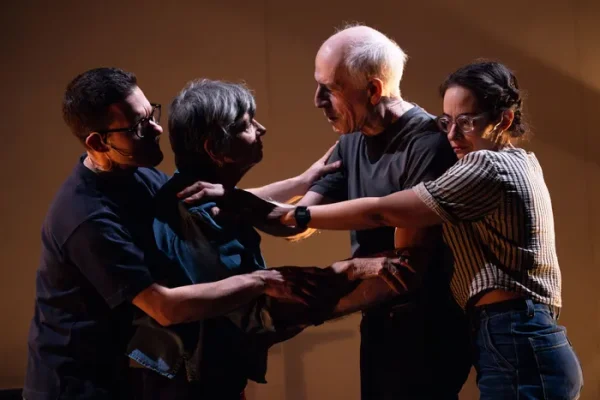

The Following Evening: Two married couples – Paul and Ellen, Abby and Michael – different generations, different ages, different life stages, grandparents and about-to-be parents, “experimental” theater makers balancing art and domesticity; the universe in a teacup, landmarks and memory, shifting geographies of the city, mind and spirit; the familiar patterns of patter and care at home, conversations and shorthand. What merits our attention? What does a life in the theater look like? What does a life well-lived look like?

ELLEN: (shouting) ALL I’VE EVER DONE IS THIS ONE THING IN MY LIFE. I’D LIKE TO THINK IT WAS NOBLE, NOT FOOLISH.

How do we learn to live from each other, with each other?

PAUL

I thought I would be a doctor.

I thought it was a natural place for my curiosity.But I had a friend who was in a play.

Someone dropped out, and would I step in, would I be interested.I memorize the lines in one afternoon.

And out there

On the stage

With a hundred eyes watching I begin.

Paul was in the Open Theater. That’s where he met Ellen, in 1970. She was an intern, from California. Paul is from New York; his great grandmother was born in New York in 1863. (I learned that from the show).

When I first met Paul, actually met him for a real conversation, not just casually in the lobby of a show or something, it was 2013. Deborah’s friend and collaborator Suli was in the Talking Band Show Marcellus Shale, and I really liked it. Wanted to learn more. I didn’t realize, I think, the connection, that Paul and Ellen had been in the Open Theater, that Talking Band was founded in 1974 after The Open Theater disbanded.

Paul dropped out of med school to take up a life in the theater.

My dad was a doctor, about the same age as Paul.

I took up a life in the theater, or at least I tried.

Paul and Michael are seated now moving together

PAUL

Do you mean – are you asking if things were better?Well.

There was – when we first started – we felt all this possibility.

It was 1967. 1968.

We had this sense that we could try anything and people would come to see what we were doing.

It was questions.

Can we do it like this?

Can we live this way?

Can we work like this?MICHAEL

Hunh.

And I’m just trying to figure out –

I’m, I don’t know.

Out in space

Un

UnABBY

UnnecessaryMICHAEL

UnnecessaryPAUL

You have different things to deal with. You have your questions, we had ours.MICHAEL

But I don’t have any horn to blow. I’m just some scarecrow

You two had all of this –(pause)

PAUL

It isn’t so clear cut: the way things were and the way things are.MICHAEL

I know.

But you were pioneers and we are just –

Jerks.(silence)

I used to go to shows all the time. Five nights a week for over a decade. I worked at a theater. I started Culturebot. You get to know people.

Abby was in all the Witness Relocation shows. Then she and Michael started 600 Highwaymen. I went to their shows. Talking Band wanted to redesign their website, Abby was designing websites, a connection was made, though I imagine they knew each other before that, because Tina Shepard from Talking Band taught at NYU Tisch, which is where Abby and Michael studied, I think. But anyway, this was also 2013. I think.

One might not, at first glance, imagine a connection between the work of Talking Band and 600 Highwaymen but then, this, from The Following Evening:

ABBY: I picture a large group of people on an empty stage. Not empty. They’re building something, and they’re totally absorbed in what they’re building.

The thing the group is doing is a means of –. It’s a way to remind themselves that a kind of beauty is possible.

The shape of the thing changes over time, the strategies change, but the central questions – ways of thinking about theater and being in the world – persist. The thing about theater is that performances, plays, exist outside of time, outside of the material world. A script is a prompt, a score. A performance doesn’t exist until it is embodied and enacted. The learning from generation to generation isn’t confined to the text but the shared work of making the abstract real in space over time. It is materially ephemeral, enduring in memory.

PAUL:

The plays are made entirely of snow. Turn to water.

Then to ice.

Stay a little while longer.

Then gone.

The Following Evening operates in ellipses, in fragments, snapshots of moments. It is recursive. Slippery. Like memory. We are in Paul and Ellen’s Soho loft where they made their shows and raised their family, where neighbors have come and gone, where they are the sole remaining artists surrounded by financiers and tech moguls. We are with Abby and Michael driving through an unnamed desert. We are with the four of them, in the loft, rehearsing the same show we are watching, we are in the loft at some indeterminate time in the future – or maybe the recent past? – and the skylight that Paul made when he and Ellen first moved in is now smashed. .On the floor is a perfect square of snow.

I don’t know how to write about this show for a general audience. Or rather, I don’t want to. I thought it was a great show. I was deeply moved. I hope that it tours to other places and other audiences get a chance to experience it. But I’m not going to try to convince anybody about why the show was good, why these artists important, why this story is significant. I’m not sure anyone can be convinced of anything anymore.

What I will offer, all that I can offer, is this: theater, at its best, takes us out of the quotidian and into the liminal, into an experience of space and time that makes the mysteries of interconnection tangible, real.

There is a theory of Quantum Entanglement that Albert Einstein described as “spooky action at a distance” where the “aspects of one particle of an entangled pair depend on aspects of the other particle, no matter how far apart they are or what lies between them…. The strange part of quantum entanglement is that when you measure something about one particle in an entangled pair, you immediately know something about the other particle, even if they are millions of light years apart.”

Human beings are entangled. We don’t always know how, where, or across what distances, or even times – generations! – but we are endlessly entangled. Live theater is an analog technology for mapping quantum entanglement. When it works, and it doesn’t always, or even often, live performance builds the entanglement map with the audience in real time.

It is difficult work, balancing the specificity of time, place, action, gesture and intention of a performance while leaving enough space for the audience to fill in the gaps from their own memory. It is difficult to discover and establish the rhythm and pace of a performance, the sequence in which events unfold over time, for the fragments to cohere, for the audience to connect the dots on their own, in their own imaginations. It can be complex, like Einstein on the Beach or it can be as simple as a callback in a live comedy set. The artist designs the map, the architecture of discovery, but the audience completes it.

Part of what I found brilliant about The Following Evening was the way these elements nested together. We see the four performers working to discover the rhythm and pace of the performance, even as we are watching the final product. We see Paul and Ellen today, in this moment, and remembering together 1970, their first meeting. And when we are watching the show in the present, we know that the “present” we are watching is also in the past. Babies are born, relationships negotiated, time passes, meaning is made through the art of attention and juxtaposition, it accumulates and evaporates. The show is made the way that lives are lived: it is, they are, intertwined, entangled, as are we all.

The show ends and we return to quotidian time; we are more expansive, more capacious, more aware of our interconnectedness than when we entered. It seems like magic but it is not an illusion, it is not a trick. It is a glimpse into what is all around us all the time. And it is awesome.

Leave a Reply